March 21, 2013 | Press Release

Lifetime fertility on the rise

New forecast: In many developed countries the trend of falling cohort birth rates reverses. Women born in the 1970s will finally have more babies than previous cohorts.

There will finally be more babies per woman than commonly expected, MPIDR projections show. © iStockphoto.com / mathias the dread

Rostock, Germany. The average number of children women have over their lifetimes appears to be rising or to have stopped its decline in many countries characterized by low birth rates in the last decades. In many countries, including the USA, the UK, Germany, and Japan, cohort fertility has been rising recently for those women born in the 1970s when compared to earlier generations. This is the result of new projections performed by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in Rostock, Germany, for 37 developed countries with a prolonged history of fertility below the replacement-level of 2.1 children per woman. The forecasts were done with a new method developed by MPIDR demographers Mikko Myrskylä, Joshua Goldstein and Yen-hsin Alice Cheng (now at Academia Sinica in Taiwan) and have now been published in the journal “Population and Development Review”.

The forecasts are based on the number of children women born in the 1970s have already had together with a continuation of age-specific birth rates. The current recession is unlikely to have a major effect on this generation of women, who have already had most of their children. It remains to be seen if the recession will have a lasting effect on the lifetime fertility of younger cohorts.

Forecasted cohort fertility substantially exceeds the number of children per woman which is discussed in public and which demographers call a “period” fertility rate. Period fertility measures summarize the behavior in a given calendar year by summing up the age-specific fertility rates of all women aged 15 to 49 in that specific calendar year. These women do not form one true cohort of mothers, but an artificial cohort composed of women from 35 different birth years, all behaving a little differently with respect to childbearing. Specifically, the calculation of the period fertility rate does not take into account the fact that each cohort has children slightly later than the last. If this is the case, as for most low fertility countries, the period fertility rate underestimates the cohort fertility rate, which is the true number of children women from a specific birth year have during their whole lives.

For instance, the United States had a period birth rate of 1.9 children per women in 2010 after experiencing a decline below replacement level the years before. However, cohort fertility of women aged 35 in 2010 (i.e. of the 1975 cohort) is forecasted to be 2.2 by the end of their childbearing age. Cohort fertility is calculated using the woman’s year of birth and cannot be exactly computed until the end of their childbearing years. This is generally assumed to be at age 50. Therefore the latest official numbers of lifetime fertility are only available for women born in 1962. But with the new forecasting method by the MPIDR researchers it is now possible to project cohort fertility for even more recent cohorts, those which have not yet completed their childbearing years.

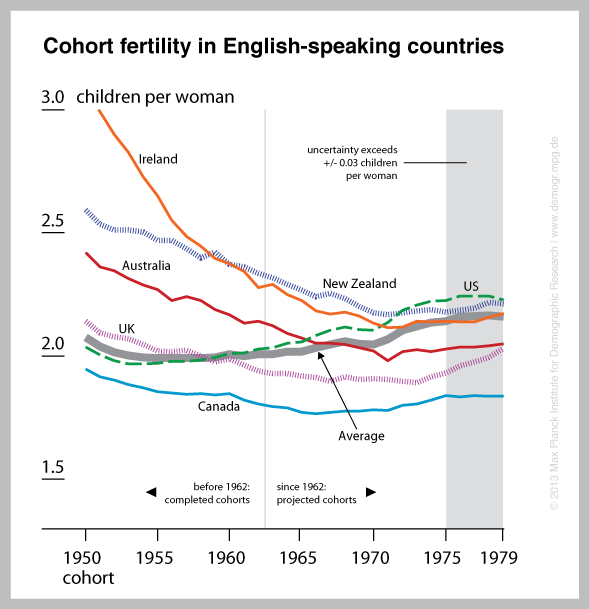

Cohort fertility is forecasted to increase steadily in the English-speaking world (download figure in high resolution (PNG File, 240 kB)). Notable are the continuous gains in the US with cohort fertility exceeding 2.0. The trend reverses from falling to rising birthrates in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Ireland for women born in the 1970s. In Canada the turnaround happens earlier, with the cohorts of the mid-60s. (See extra data sheet with figures including all 37 developed countries (PDF File, 212 kB).) © MPIDR

Cohort fertility is rising or stable in 26 out of 37 countries

Cohort fertility has now been forecasted for women born as recently as 1979. According to the forecast, in the majority of countries, 26 out of 37, cohort fertility for the late 1970s cohorts is either increasing or stable. The absolute increases in the number of children per woman will still be small. “The important point is that after decades of falling fertility we see a trend reversal in many countries,” says Goldstein. “The long-term fertility decline in the developed world appears to have come to an end in many countries.”

Cohort fertility will increase steadily in the English-speaking world. Notable are the gains in the United States and the United Kingdom, both with cohort fertility exceeding 2.0. In the Nordic and Baltic countries the lifetime number of children per woman is remarkably stable, and in Continental Europe it shows signs of reversed direction from decline to rise. In Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, decades of decrease appear to be coming to an end.

Against the general trend average cohort fertility is still falling in East Asia. But even there the decline is slowing. Cohort fertility has increased slightly for recent cohorts in Japan, which has historically been a demographic trendsetter for the region. “It remains to be seen when declines will stop in these countries,” says MPIDR demographer Mikko Myrskylä. (See extra data sheet with figures including all 37 developed countries (PDF File, 212 kB).)

Among the 37 countries, 19 had experienced period birth rates lower than 1.3 by 2009, a threshold often termed “lowest-low” fertility. On the contrary, cohort fertility averages to 1.77 children for women born in 1975 for all 37 nations. “These differences suggest that much of the observed very low fertility has been attributable to later, not less, childbearing,“ says Joshua Goldstein. Thus very low period birthrates are to large parts a mathematical effect generated by the ongoing postponement of parenthood. But that postponement does not mean parents can’t have their desired number of children later in life. And they do so to a larger extent than the low period birth rates suggest.

“Fertility trends are notoriously hard to forecast,” says Joshua Goldstein. “The recent end of a decline in cohort fertility signals an important turning point which makes some of the current long-term fertility forecasts, such as 1.3 for Japan and 1.4 for Germany, seem considerably less likely,” says Goldstein.

About the MPIDR

The Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in Rostock investigates the structure and dynamics of populations. The Institute’s researchers explore issues of political relevance, such as demographic change, aging, fertility, and the redistribution of work over the life course, as well as digitization and the use of new data sources for the estimation of migration flows. The MPIDR is one of the largest demographic research bodies in Europe and is a worldwide leader in the study of populations. The Institute is part of the Max Planck Society, the internationally renowned German research organization.

Associated Information for Download

This Press Relase (PDF File, 201 kB)

Data sheet with figures including all 37 developed countries (PDF File, 212 kB)

Figures from the datasheet:

Figure “Cohort fertility in English-speaking countries” (PNG File, 240 kB)

Figure “Cohort fertility in Nordic and Baltic countries” (PNG File, 243 kB)

Figure “Cohort fertility in Continental Europe” (PNG File, 224 kB)

Figure “Cohort fertility in Mediterranean Europe” (PNG File, 221 kB)

Figure “Cohort fertility in Eastern Europe” (PNG File, 316 kB)

Figure “Cohort fertility in East Asia” (PNG File, 263 kB)

Original publication

Myrskylä, M., J. R. Goldstein and Y. A. Cheng: New cohort fertility forecasts for the developed world. Population and Development Review [First published online: 20 March 2013]. DOI:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00572.x

Contact

PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS