July 24, 2019 | News | Publication

Census: The 1.5 million gap

The 2011 census has left a long gap in Germany’s population figures. Between this and the preceding censuses, held in the 1980s, a large number of errors thus must have crept into the official statistics. A study shows how plausible population figures can still be derived even in the inter-censal period, with relevant consequences for the development of life expectancy, too.

The following text is based on the original paper Adjusting Inter-censal Population Estimates for Germany 1987-2011: Approaches and Impact on Demographic Indicators by MPIDR researchers Pavel Grigoriev and Dmitri A. Jdanov and a German version with minor changes has also been published in the issue 01/2019 of the demographic quarterly Demografische Forschung Aus Erster Hand.)

Instead of well over 81 million, Germany had only just over 80 million inhabitants: A total of 1.5 million citizens had disappeared with the 2011 census – at least from the statistics. Although the population census received some successive criticism, legitimate in part, a large share of the "missing inhabitants" will only have existed on paper but never de facto. This is because especially migration leads to errors in the registration of in- and outflows. For instance, migrants may have been registered twice because their names are spelled differently or individuals may have moved away without de-registering. The rather chaotic conditions during German reunification in particular will have led to a large number of errors in the statistics, the authors Pavel Grigoriev, Rembrandt D. Scholz, and Dmitri A. Jdanov from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock and Sebastian Klüsener from the Federal Institute for Population Research in Wiesbaden write in their study.

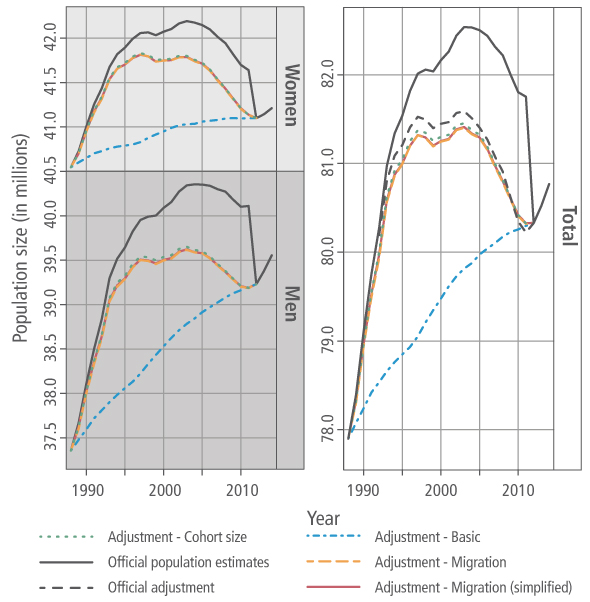

Fig. 1: The basic approach, often used for less complex cases, does not provide plausible results for Germany. All other calculation methods for population development between 1987 and 2011 yield rather similar results and, especially from 1995 onwards, are well below the official figures.

© Source: Federal Statistical Office, own calculations.

The 2011 census revealed these errors. The over 90-year-old male population in West Germany showed deviations of more than 35 percent. Even in the age group 20-50, and especially among men, the old figures were up to five percent higher than the newly derived ones.

The 2011 census was the first so-called register-based census carried out in Germany; it is based on population register data and verified by random. But given the new official figure of 80.2 million inhabitants in Germany, the question naturally also arises as to how the numbers on population development in the long inter-censal period should be adjusted backward. This is because not only the old numbers for 2011 will have been wrong. The last census in West Germany was carried out in 1987 and the last census in East Germany was held back in 1981. In the inter-censual period, the errors must have accumulated.

In their study, the demographers thus present four different approaches to produce backward-adjusted population estimates for the years between the censuses. They used the same time period both for East and West Germany for their calculations: 1987 to 2011.

The first, fairly simple "basic approach “does not account for migration. It starts from the assumption that the errors have accrued evenly over time. It yields no plausible results (see Fig. 1). This is not surprising as migration movements were the main cause of large fluctuations and errors during the period studied. They were very high especially around the time of German unification. The other three approaches yield results that differ only marginally. Two of these approaches account for the fluctuation in migration intensities over time in different form. The last approach, by contrast, only controls for changes in the size of an observed birth cohort over time. This is based on the assumption that the detected error rate per year is dependent on the number of individuals in a cohort in that year. Let's say, for example, that the adjustment period would be two years, with a cohort of 2,000 individuals in the first year and 1,000 persons in the second year, and the newly derived error value be 300 individuals. Then it would be assumed that 200 errors were to have emerged in the first year and 100 errors in the second year. This approach yielded results similar to those of the far more complicated approaches based on migration data. The authors thus finally decided for this very method. The newly derived and adjusted population figures were also used for the recalculation of life expectancy.

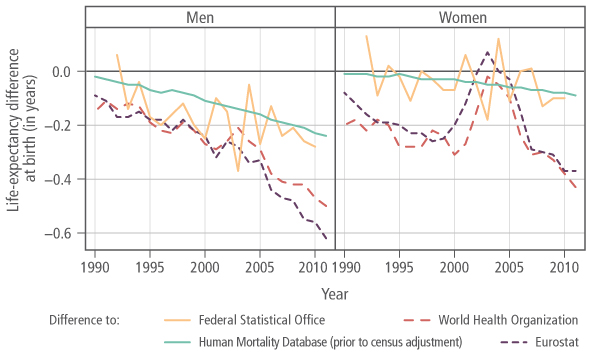

Fig. 2: Life expectancy in Germany was probably much lower than had been previously assumed, most notably at the end of the study period. The calculations by the Federal Statistical Office, the World Health Organization, Eurostat, and the Human Mortality Database (prior to census adjustment) provide values that are all higher than the average life expectancy, now calculated on the basis of the newly derived population data. © Source: Federal Statistical Office, WHO, HMD, Eurostat, own calculations.

And indeed, the new calculations done by the four demographers show: At the end of the adjustment period, the life expectancy among the men was up to seven months lower and that of women up to five months lower than in the calculations based on the unadjusted figures published originally (see Fig. 2).

Co-author of the scientific study: Pavel Grigoriev

Scientific article: Klüsener, S., Grigoriev, P., Scholz, R. D., Jdanov, D. A.: Adjusting inter-censal population estimates for Germany 1987-2011: approaches and impact on demographic indicators. Comparative Population Studies, 43, 31-64 (2018). DOI: DOI:10.12765/CPoS-2018-05en