July 14, 2014 | News | New Publication

No child day care services, no children

Women in Germany have low fertility levels mainly due to a lack of public day care services for children

In the past, many demographers concluded, that the low fertility levels in Germany are primarily the result of a specific cultural imprint. A MPIDR study suggests that these assumptions do not hold. © suschaa / photocase.de

(The following text is based on the original article "No child day care services, no children" by MPIDR researcher Sebastian Klüsener has also been published in the issue 02/2014 of the demographic quarterly Demografische Forschung aus Erster Hand.)

Compared to Europe, Germany has been reporting relatively low fertility levels for decades. The primary determinants are not cultural factors, however, but rather shortcomings in family policy – as shown by a cross-country comparison with the German-speaking regions in neighboring Belgium done by scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Demographic Research in Rostock.

Life without children: Some couples prefer this to the everyday stresses and strains that having a family brings. They enjoy their job, and the luxury and freedom that come with a lifestyle without children. The so called “Dinks” (double income, no kids) enjoy a high prestige, and do so especially in German-speaking countries.

In the past, many demographers thus concluded, that the low fertility levels in Germany are primarily the result of a specific cultural imprint. A study by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany now suggests that these assumptions do not hold.

A team led by Sebastian Klüsener has shown that women living in the Belgian regions shaped by German culture have significantly more children than women in Germany. Belgium has a well-developed child care system, but not so Germany. And herein lies the main reason behind Germany’s lack of children, according to Klüsener and his colleagues: There are too few day care facilities for children.

The demographers looked at data from two representative household surveys: the Belgian census of 2001 and the German microcensus of 2008, comparing the birth rates of women born 1935-59 in Germany, Belgium, and especially the two eastern Belgian districts of Eupen and Malmedy. The two districts are bordering Germany and German is the official language.

The community’s 75,000 inhabitants speak German at home and at school, they regularly turn to German mass media, and there is frequent contact to relatives across the border. For close to a century now, they have been benefiting from Belgian family policies.

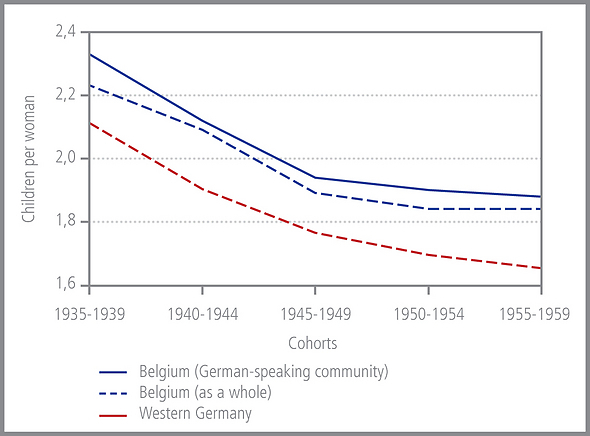

"If cultural norms were decisive in affecting the birth rate, we would expect the fertility of the German-speaking community to resemble that of the populations in Germany”, says Klüsener. But the facts prove different: West German women born 1955-1959 had on average 1.65 children by the time they reached age 50, compared to 1.88 children for the reference cohort in Eupen and Malmedy. This is slightly above the figure for the rest of the country, which stands at 1.84 children for their Belgian peers (see Fig .1). And, most notably, women all over Belgium became third moms more frequently so than in Germany.

Fig. 1: Women in the German-speaking regions of Belgium (less German citizens and those born in Germany) have on average as many children as Belgians women. In Germany, the birth rate is significantly lower. © Sources: Belgian Census 2001, German micro census 2008, own calculations.

"A key element in determining the final number of children per woman seems to be a high level of institutional childcare, rather than the practiced German culture," says Klüsener. While the development of family allowances and parental leave schemes unfolded similarly in the two countries, substantial differences continue to persist in child care coverage.

Belgium has been expanding child care coverage continually since 1950. The result is, inter alia, that some 20 years later, some 95% of children under age 4 were in child care compared to a third in Germany. The gap* is persisting to date: In 2008, 43% of all children aged under 3 and living in Belgium were in formal child care. In Germany the figure stands at 10%.

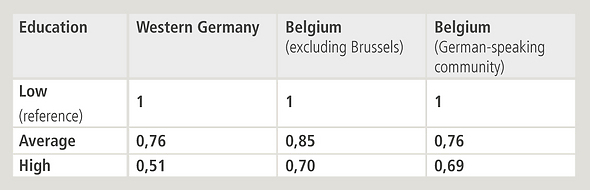

Other effects on the birth rate could largely be excluded by the researchers around Klüsener. It is well known, for example, that highly educated women generally have fewer children. This correlation is also evident in the current study: The more highly educated the women were, the higher the odds that they remained childless. The effect is much more pronounced in Germany, however, than it is in the German-speaking regions of Belgium and in the rest of the country (see Table 1).

Table 1: The table shows the effect of education on the odds of having at least one child in their life for women in the regions under study. The more highly educated the women are, the higher the chances that they remain childless. In Belgium this effect is less pronounced than in western Germany. All values are considered highly significant. © Sources: Belgian Census 2001, German micro census 2008, own calculations.

"We know from other studies, that access to child care is particularly relevant for highly educated mothers," says Michaela Kreyenfeld, who was involved in the study. "Our results fit this picture." The Belgian child care system seems to support the decision of couples to have a life with children as it facilitates the reconciliation of family and work”, the demographers conclude. It is little wonder, then, that at the beginning of the millennium almost two-thirds of mothers with children aged 0-2 and living in Eupen or Malmedy were gainfully employed, compared to just a third in western Germany.

Co-author of the scientific study:

Sebastian Klüsener

Based on this scientific study:

Sebastian Klüsener, Karel Neels, Michaela Kreyenfeld: Family Policies and the Western European Fertility Divide: Insights from a Natural Experiment in Belgium. Population and Development Review 39(4): 587–610 (Dezember 2013)

DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00629.x

Online version