January 11, 2024 | News | DeFo-Article

Unequal Distribution

Working life in Germany is getting longer – but not equally so for all population groups

Current pension and labor market policies aim to keep people in work for longer. But not everyone benefits equally from these regulations.

The time a person spends working during his or her lifetime is getting longer in Germany. © iStockphoto.com/ferrantraite

The extension of late working life is seen as a potential remedy to address the challenges of an aging society. The idea is that if people spend more time of their life in paid employment, they will also pay higher pension contributions. Whether this works essentially depends on whether and, if so, how much time people spend in their final job before reaching retirement age, among other things. A team of researchers led by Christian Dudel from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research has now conducted a study on employment during to this stage of life, an issue we still know very little.

Many of the labor-market policies introduced in the last decades focused on the final stage of working life. Current regulations and legislations primarily aim to keep people in work for longer. But before then and for a long time, rather the opposite applied: to encourage older workers to leave the labor market in order to make room for the younger cohorts, the baby boomers. To this end, regulations made early retirement more attractive. In West Germany of the 1980s, for example, working people could leave paid employment at age 58, draw unemployment benefits for two years, and then retire at age 60. It was relatively easy then to get a disability pension granted, which later could be converted into a regular old-age pension at age 60 without deductions.

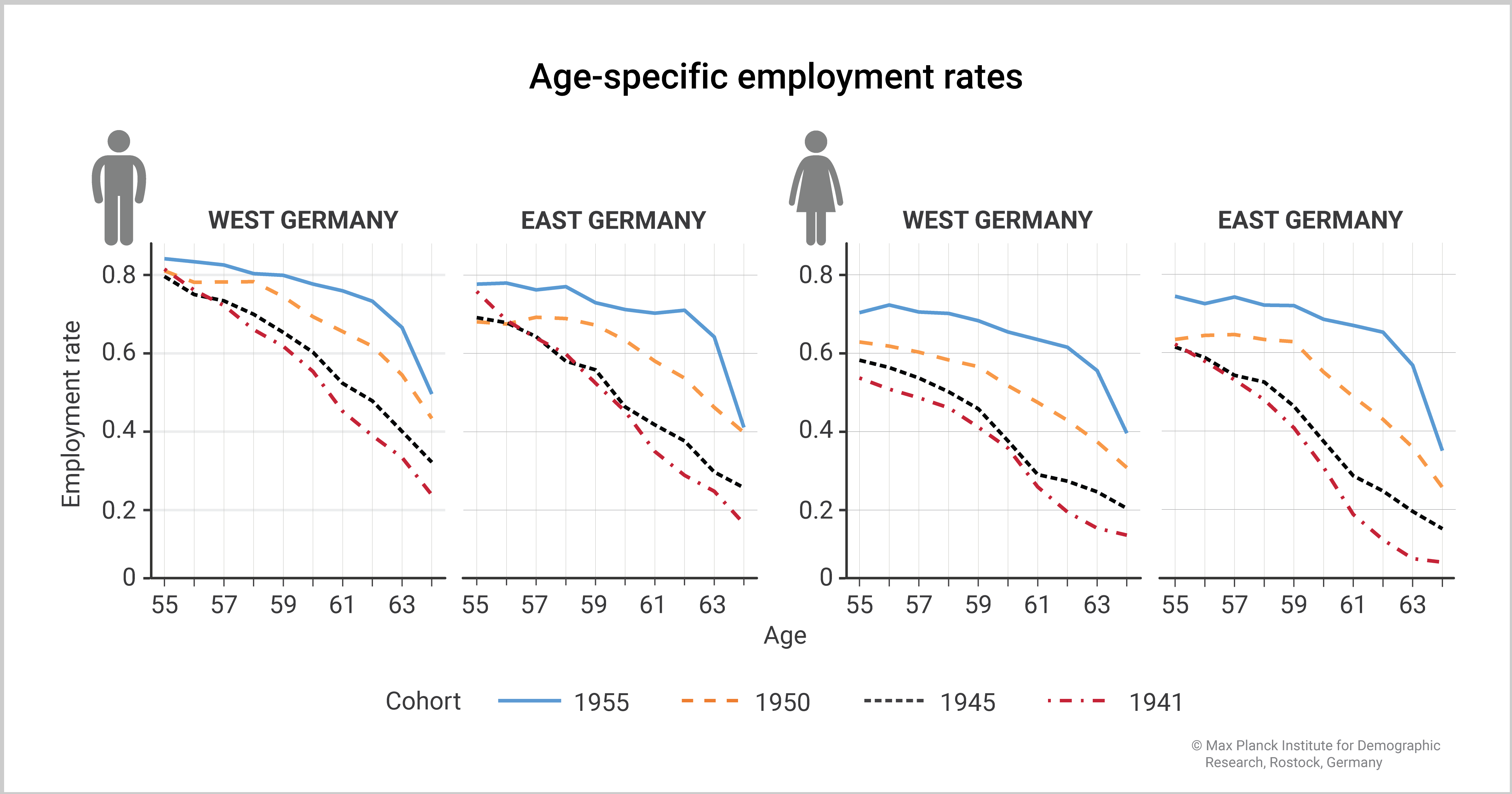

Age-specific employment rates ages 55 to 64. Overall, late working life is increasing by age group. Source: Microcensus, authors´ calculations. © MPIDR

But the tide began to turn from the 2000s onwards. It emerged that the aging population would become a major problem for Germany’s pay-as-you-go pension system because the German population is among the oldest in the world: The share of the population older than 67 is expected to increase from 19% in 2018 to 26% in 204 — while the size of the workforce is expected to decline. The measures to tackle the imbalance again primarily aimed at the last phase of late working life: Between 2000 and 2009, the statutory retirement age for women was raised successively from 60 to 65 and is now set to increase in stages from 65 to 67 by 2031 for everyone. Also, a series of reforms made early retirement less attractive. Currently, employees cannot retire until they reach age 64 (with a few exceptions) and must then accept reductions in pension benefits.

The researchers wanted to find out whether the pension and labor-market policies have truly led to working lives getting longer and people working to higher ages. But it was equally important for them to puzzle out whether every population group is equally affected by the policies or equally benefits from them. They used data from the German Microcensus for their study and looked at working ages 55 to 64 of birth cohorts 1941 to 1955.

Their results showed that the length of working life has been increasing continuously in Germany: across the birth cohorts studied, for both men and women, and in eastern as well as western Germany (see Fig. 1). The findings are consistent with the trends in employment rates at older ages. These have been rising steadily since 2000, as shown by other studies. But it is difficult , the authors say, to distinguish the reasons behind: the reforms or rather the overall strong performance of the German labor market. The steady increase in educational attainment may also have an influence.

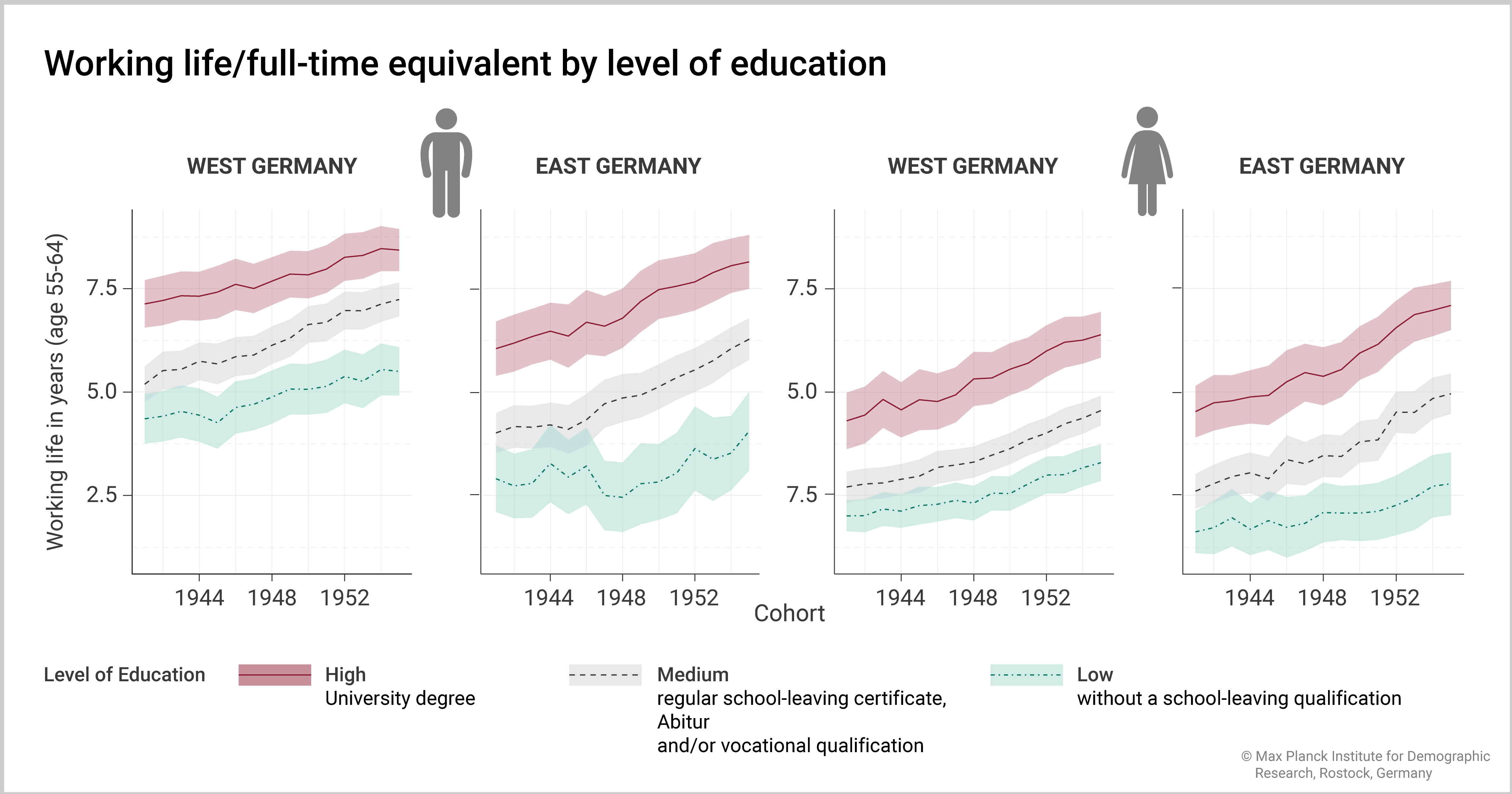

But the study also reveals very large disparities between different socioeconomic groups: For example, highly educated men in western Germany work on average three times as many years as eastern German women with a low education level (see Fig. 2). Some groups have also seen much slower growth in late working life than others. Especially low-educated men and women in eastern Germany run the risk of falling behind, as do men in both parts of the country who have elementary or unskilled jobs, the researchers write.

How much time people spend at work depends heavily on their level of education. Women in eastern Germany with a low level of education fare particularly badly. Source: Microcensus, authors´ calculations. © MPIDR

Striking but also to be expected are the gender differences: Men work more years than women, and employment rates for women are much lower throughout. This is due to the German tax system, which favors the male breadwinner model. Also, it is still difficult for women to reenter the labor market after leaving work to raise children.

As to education and occupational qualification, the researchers discovered that having a higher level of education and a higher occupational qualification correlates with longer late working life. This is likely due to several reasons: Low-qualified workers have a higher risk of unemployment. They cannot offset the risk by staying in the labor market longer because the insider‒outsider nature of the German labor market makes it more difficult for the older unemployed to find a job. It is also still common for work contracts to terminate at the statutory retirement age, and this makes it difficult for some older people to work longer in the same job. Older people are also sometimes unable to continue work in physically demanding jobs.

A challenge for the future thus is to initiate policies that enable people to work longer while not widening the inequalities between the different occupational groups and not disadvantaging people with low occupational qualifications, the authors say.

Original Publication

Dudel, C., E. Lochinger, S. Klüsener, H. Sulak and M. Myrskylä: The extension of late working life in Germany: trends, inequalities, and the East–West divide. Demography 60(2023)4, 1115–1137. DOI: 10.1215/00703370-10850040