November 03, 2022 | Press Release

Falling Birth Rates in Northern Europe

Fertility declined, especially among younger women and in more rural areas. © Miss X / photocase.de

Birth rates in Scandinavia used to be the highest in Europe for long, but since 2010 they have declined faster than expected, such as in Finland where they have slumped to an all-time low. A study by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research now investigates the extent to which there are differences in fertility at the sub-national regional level.

Family-friendly social benefits, sufficient childcare provision, and high levels of gender equality between men and women: For long, the Scandinavian countries served as role models for modern family policy and even upheld this role in the years surrounding the 2008 economic crisis, as birth rates remained relatively high.

But since 2010 birth rates have also fallen in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Prior explanations focused on economic factors (such as unemployment) and social factors (such as values and expectations). A new study by Nicholas Campisi and Mikko Myrskylä from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Hill Kulu and Júlia Mikulai from the University of St. Andrews, and Sebastian Klüsener from the Federal Institute for Population Research examines the extent to which these factors play a role at the sub-national regional level.

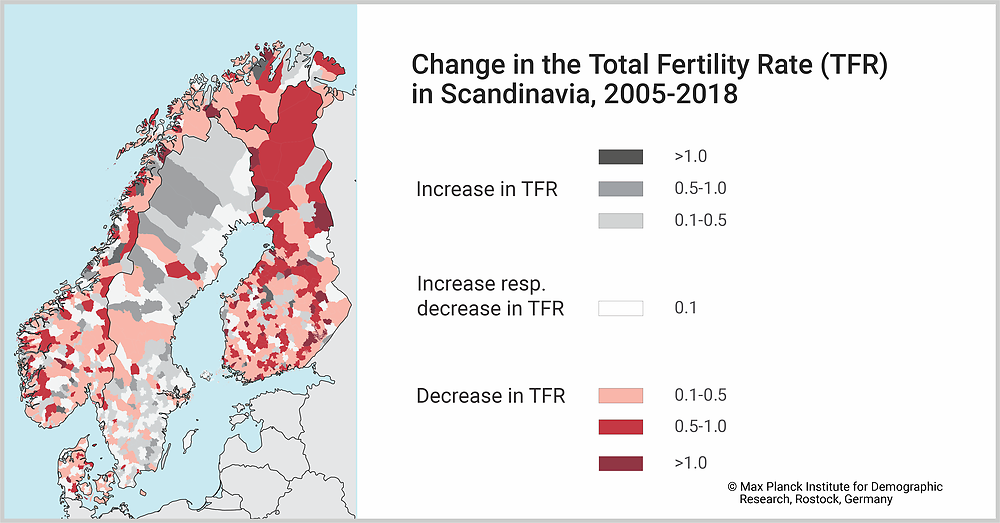

Analyzing fertility data for more than 1000 municipalities and covering the years 2005 to 2018, the authors discovered large divergencies by level of urbanization.

The birth rate fell rapidly in some Finnish municipalities, in part by more than one child per woman.

Download Figure (PNG File, 1 MB)

Overall, these differences are largest in Norway and Finland. This is also where birth rates declined the most. Sweden’s birthrates, by contrast, hardly changed; Denmark showed a slight decline. The expected urban-rural gradient in fertility levels is observable in all Nordic countries.

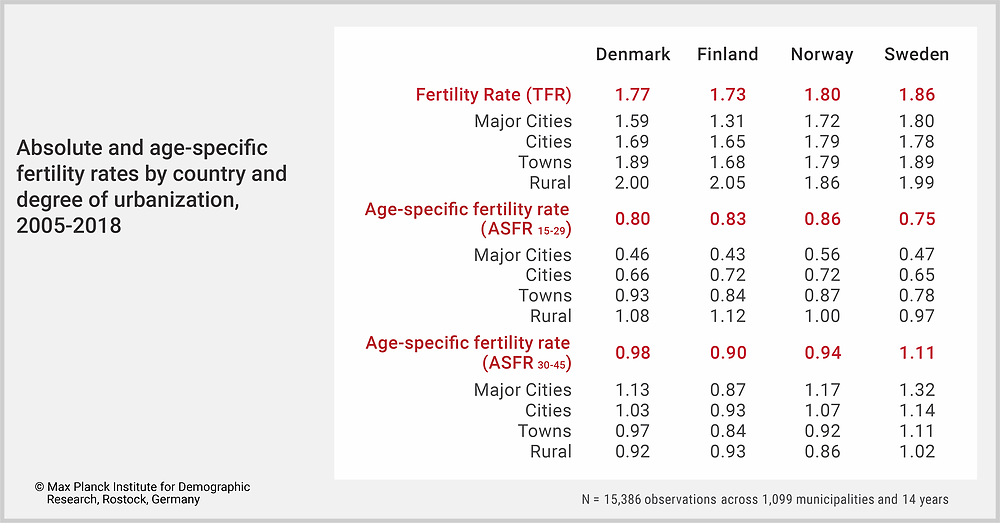

The birth rate among older women is especially high in the classic major cities, but younger women in rural municipalities have more children. © MPIDR

Download Figure (PNG File, 363 kB)

Rural municipalities (less than 50,000 inhabitants) saw the highest birth rates, for the most followed by town municipalities (up to 100,000 inhabitants), city municipalities (up to 500,000 inhabitants), and finally the classis major cities (over 500,000 inhabitants).

But when the researchers examined the birth rates of 15- to 29-year-old women and 30- to 45-year-old women separately, they mainly observed a reversed pattern. In Denmark, Sweden and Norway, the classic major cities rank highest in this group because women generally have children later there.

The researchers have also shown that younger women experienced the largest decline in birth rates. The decline is overall mitigated by slightly rising or at minimum relatively stable birth rates for older women. Finland’s slump in birth rates was mainly due to fertility decline among 30- to 45-year-old women. If this happened in the other three countries, a further decline would be expected, writes the team of researchers.

The researchers used additional data to examine the extent to which different economic or social conditions in the studied municipalities explain the development of birth rates: They surveyed the share of the economically inactive, the share of dissolved partnerships, the share of highly educated women, and the share of votes for conservative parties, as well as per capita income and the net migration rate. As expected, a high proportion of the economically inactive negatively affected the birth rate – but less so than assumed.

Also surprising was that higher per capita income correlated with lower birth rates both among the older and the younger women. Especially for the latter it was assumed that greater economic stability would have a positive effect on the birth rate.

Overall, however, social factors were at least as important as economic ones. For example, high separation rates in the municipalities for the most led to significantly lower birth rates, whereas a high share of votes for conservative political parties was associated with higher fertility.

Original Publication

Campisi, N., Kulu, H., Mikolai, J., Klüsener, S., Myrskylä, M.: A spatial perspective on the unexpected nordic fertility decline: the relevance of economic and social contexts. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s12061-022-09467-x

Authors und Institutions

Nicholas Campisi, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock; University of St Andrews

Hill Kulu, University of St Andrews

Júlia Mikolai, University of St Andrews

Sebastian Klüsener, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock; Federal Institute for Population Research, Wiesbaden; Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas

Mikko Myrskylä, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock; University of Helsinki