October 23, 2018 | News

The economic crisis led to a sharp decline in working life expectancy in Spain

In times of demographic change, raising the retirement age is often discussed. But the length of our working lives depends to a large extent on how continuously we work. In Spain, for example, working life expectancy fell sharply during the economic crisis, a study by the MPIDR has shown.

The following text is based on the original papers The length of working life in Spain: levels, recent trends, and the impact of the financial crisis by MPIDR researchers Christian Dudel and Mikko Myrskylä and The legacy of the great recession in Italy: a wider geographical, gender, and generational gap in working life expectancy by MPIDR researchers Angelo Lorenti and Mikko Myrskylä has as a German version with minor changes also been published in the issue 3/2018 of the demographic quarterly Demografische Forschung Aus Erster Hand.)

Those who live longer also have to work longer – this is the simplified formula that sums up the challenges that come with demographic change. If shortfalls in the social security system are to be avoided, then the years spent working – and not just the years spent in retirement – have to increase. For this reason, raising the retirement age is often discussed.

But in such discussions there is a tendency to lose sight of the reality that a range of factors influence how many years of our lives we spend working. First, entry into the labor market can be delayed by a longer period of time spent in education. Second, over the course of our lives, breaks in employment for health or family reasons, or because we can’t find work, can add up.

What effect rising unemployment can have over time on the average working life is an issue Christian Dudel und Mikko Myrskylä of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research have explored in two studies. Both focus on countries that have recently been struggling with relatively high unemployment. Together with their colleague Angelo Lorenti, they found, for example, that in Italy between 2003 and 2013, the length of working life decreased substantially, and the differences between men and women and between the wealthier north and the south grew.

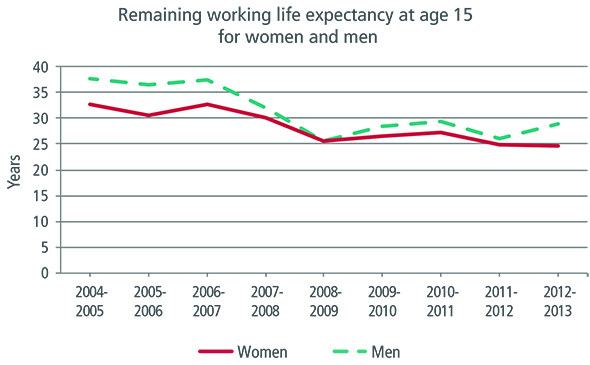

Fig.1: During the economic crisis in Spain, working life expectancy decreased substantially. Starting with current labor market data, the working life expectancy of 15-year-olds is calculated by subtracting the years spent in education, unemployment, and retirement from total life expectancy.

© Source: Continuous Working Life Sample (CWLS) 2004-2013, own calculations.

In a second study, Dudel and Myrskylä, together with María Andrée López Gómez und Fernando Benavides of the University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, investigated the effects of the economic crisis on the length of working life in Spain.

In an analysis of data on more than a million Spaniards from the Continuous Working Life Sample (CWLS), the four researchers estimated the working life expectancy.

Around the year 2008, Spain entered a severe economic crisis, which led to a significant decline in the working life expectancy (see Fig. 1). Whereas in 2004/2005 men could expect to work nearly 38 years, this relatively high figure in the European context fell sharply within a few years. Based on the labor market conditions in 2008/2009, men in Spain could expect to work only around 26 years over the life course – a reduction of 12 years. The working life expectancy among women also declined considerably. While women could expect to accrue an average of 33 working years in 2004/2005, by 2008/2009 this figure had fallen to the same level as that of men: 26.5 years.

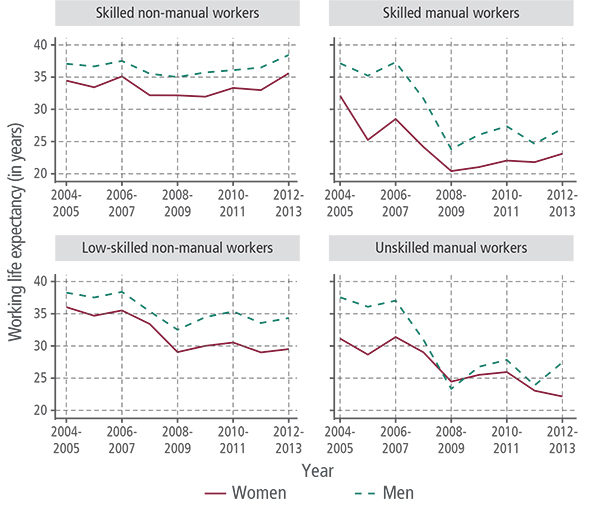

Fig. 2: Whereas the working life expectancy of skilled non-manual workers barely declined, it decreased very sharply among unskilled and manual workers, and hardly recovered after the crisis. © Source: CWLS 2004-2013, own calculations.

Unskilled manual workers were hit especially hard by the decline (see Fig. 2). In this occupational group, working life expectancy fell by around 14 years for men and around nine years for women. By contrast, skilled non-manual workers were, for the most part, unaffected by the economic crisis. While working life expectancy in this group decreased slightly at certain points, by the end of the study period working life expectancy was 38 years for men, and had even risen slightly from 2004 to more than 35 years for women. Positioned between these two occupational groups are the unskilled non-manual and the skilled manual worker categories. Workers in the latter group were more affected by the crisis than the unskilled non-manual workers. The study’s authors attributed this difference to the greater impact of the recession in Spain on manual work activities, such as in the construction sector.

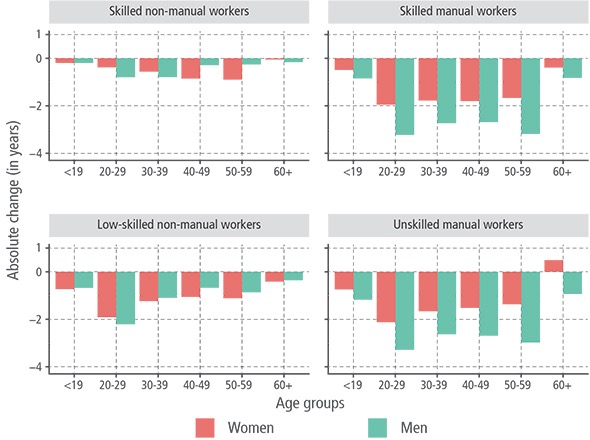

It is often assumed that the crisis hit young people trying to enter the labor market the hardest. However, this assumption was only partially confirmed by the analysis (see Fig. 3). It is indeed the case that in most of the occupational groups, the decrease in working life expectancy was greatest among those between the ages of 20 and 29. However, the decline among the 20- to 29-year-olds was clearly higher for unskilled non-manual workers only. In the remaining occupational categories, the other age groups experienced decreases of similar magnitudes. Moreover, among female skilled non-manual workers, the younger age groups actually experienced the smallest decline.

The life phases in which people are not working are not necessarily periods of unemployment. It is possible to spend periods of time in inactivity outside of retirement while receiving neither pension nor unemployment benefits. People may, for example, have life phases prior to retirement in which they are not in education and do not meet the requirements to receive unemployment benefits.

The four researchers calculated the expected time spent in inactivity as well. Whereas in 2004 girls who were 15 years old could expect to spend only 12 years of their remaining lives in labor market inactivity, at the highpoint of the economic crisis in 2008/2009, this figure had risen to 18 years. Over the same period, the expected length of time spent in unemployment rose from three to 5.4 years (2008/2009). The situation for men is similar. While in 2004 15-year-old boys could expect to spend nearly six years in inactivity, this figure had more than doubled by 2008/2009, to 14.6 years. Over the same period, the expected time spent in unemployment rose from 2.4 years to 6.7 years. However, the length of time 15-year-old boys or girls could expect to spend in retirement increased only very slightly between 2004 and 2013. The authors attributed this finding to a reform enacted in 2013 that ensured that the number of years spent in retirement would, at least, remain the same.

Fig. 3: The decline in the length of working life between 2006/7 and 2008/9 is attributable to reductions in all age groups. However, the 20-29-year-olds and the 50-59-year-olds were the most affected. © Source: CWLS 2004-2013, own calculations.

However, the values calculated for single years are never more than snapshots. Researchers can only estimate how the life of a 15-year-old will unfold if the conditions of each calendar year studied remain the same in the future. It is therefore entirely possible that younger people will end up accruing far more working years over their lives if economic conditions improve. On the other hand, it has been shown that people who spend longer periods in unemployment subsequently face greater challenges on the labor market. Thus, the authors of the study emphasize that the significant loss of working years during the crisis is a clear cause for concern, especially since the social security system of Spain, which is already burdened by the aging of the popular, will be placed under greater pressure.