May 15, 2018 | News | New Publication

Development can reverse fertility declines

The long-standing rule that wealthier populations have fewer children is not true anymore for Europe. Today regions with higher income have higher birth rates, a new MPIDR study shows.

Chances are high that within Europe rising income will in the future no longer lead to lower fertility rates, say researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock and the Freie Universität Berlin. It is a widely held belief that the number of children decreases when populations become more prosperous.

This observation was true for most of the 20th century, when birth rates were falling far below two children per woman in virtually all advanced developed countries. However, new regional data for 20 European countries over the last three decades show that this old observation no longer holds. Today, European regions with higher income tend to have higher birth rates.

MPIDR researchers Sebastian Klüsener and Mikko Myrskylä together with Jonathan Fox from the Freie Universität Berlin have now published their study in the European Journal of Population. Jonathan Fox is first author of the scientific publication and was a scientist at MPIDR, when he started working on the paper.

The shift in the relationship between development and fertility in Europe’s regions is also in the focus of a new research network initiated by the MPIDR, called “Register-Based Fertility Research Network”

Income turned into a driving force for fertility during the last 20 years

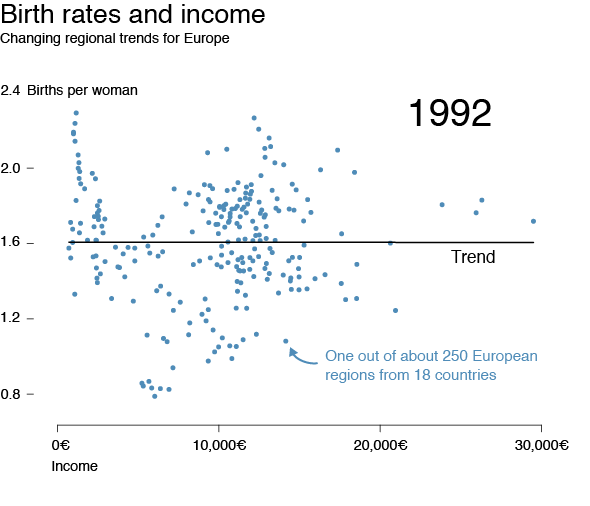

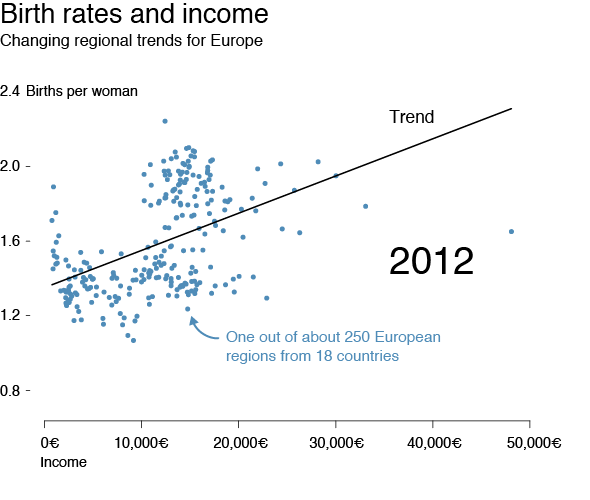

Analyzing about 250 European regions, Klüsener, Myrskylä and Fox detected a positive relationship between birth rates and income at high levels of development. This relationship can be observed both across whole Europe (see trend line in the plot for 2012 below) as well as within an increasing number of European countries. The positive trend emerged only recently and was not existing a few decades ago (see plot for 1992).

No trend in 1992: On average birth rates neither rose nor fell with income per capita. Data: National statistical offices, Cambridge Econometrics

© MPIDR

The researchers measured yearly income as the gross amount of wages paid by employers per inhabitant.

Analyses of individual countries showed that in 2012 there were still a number of countries left which reported across their sub-national regions a negative relationship between income levels and levels of fertility. But almost all countries that displayed a negative tendency in 1990, have experienced a lessening or turn-around in the relationship during the last 20 years.

Positive trend in 2012: On average over about 250 European regions of the study birth rates increase with income per capita. Data: National statistical offices, Cambridge Econometrics

© MPIDR

“These findings can change our perspective on the future of population size and population aging,” says Mikko Myrsykylä. In the past demographers and policy-makers were puzzled by the so-called demographic-economic paradox, as populations or groups within populations with higher income and education tended to have fewer children, although they had more resources available. This had led some scientists to envision scenarios in which birth rates inevitably fell and stayed far below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman as long as increases in economic development prevailed. This resulted in projections of rapidly shrinking and aging societies with a declining desire for children and an emerging culture of childlessness.

“Remarkably, our results indicate, that development is no longer acting as a contraceptive for developed regions, but could potentially promote higher fertility,” says MPIDR researcher Sebastian Klüsener. This could very well change regional patterns of fertility. High-developed metropolitan areas which had below-average birth rates within countries in the past might become fertility hot spots of the future. However, such tendencies towards a turn-around do not necessarily need to happen at a fertility level of two children per women, but can also occur at lower levels.

More children by more childcare, teleworking, and migration

According to the researchers’ theoretical considerations, the turnaround in the fertility-economy relationship is facilitated substantially by enhanced family policies and more flexible working arrangements, which allow to reconcile work and family. “Even in areas with very low birth rates people have always wanted more children,” says demographer Mikko Myrskylä. “Now modern policies and working arrangements are taking effect, enabling them to have the larger families they desire.”

The researchers believe that the most important change in family policies is a shift from providing money like child allowances by a new generation of policies targeted at directly helping working families by providing money and time. “It is especially for the higher educated helpful to expand childcare outside the home and extend parental leave schemes which are linked to prior income levels, and guarantee a return to the old job, all of which give both parents security for their future career,” says Mikko Myrskylä. “This is important as the share of women who do not want to risk future career options due to motherhood is drastically increasing in many countries,” Myrskylä adds.

Combining work (and thus income) and family is also supported by less rigid modern working arrangement such as teleworking, flex-place, or flex-time, which free parents from being present at their regular work site full time, and more easily allows them to spend more time with the family. “To some extent work is coming home again”, says Demographer Sebastian Klüsener. “Just as industrialization made people leave home for work in the 19th and 20th centuries, technological advancements like the Internet are changing the spatial organization of work in the 21st century.”

Another important factor are migration trends. Highly developed areas are attractive migration destinations both from abroad as well as from within countries. Migrants are usually more healthy than the average population, which tends to have a positive effect on fertility outcomes. Another factor are tempo-effects, as migrants frequently postpone their childbearing plans until they have settled down in the new country of residence. Peripheral areas, on the other hand, are often characterized by outmigration of highly educated and active people with potentially negative consequences for partner markets and fertility levels.

Fuel for the debate on our demographic future

In a seminal Nature paper published in 2009, MPIDR director Myrskylä had already indicated a turnaround in the birth rate-development relationship at high levels of development by comparing countries worldwide. The new study shows that shifts towards a positive relationship at high levels of development are also visible within countries across Europe. In their paper the authors also address critics who argue that the turnaround is mainly an artifact due to massive increases in the average age at birth in the developed world. In many industrialized countries women are postponing motherhood to higher ages, which temporarily decreases birth rates. But even after accounting for such timing effects, the new study obtains a positive relationship between fertility and income. Evidence is increasing that the days of the demographic-economic paradox are numbered.

Population data for Europe’s regions

The study investigated up to 263 European regions in 20 countries from 1990 to 2012. Regions were classified using the “NUTS-2” system of the European Union that splits countries into areas with between one million and three million inhabitants. Income was measured as “employee compensation per capita”, which is the gross amount of wages paid by employers, including extra payments like social security contributions, divided by the number of inhabitants per region. Income was calculated in Euro values of 2005. Birth rates were actual per-year values (total fertility rates). All data were provided by Eurostat, national statistical offices or Cambridge Econometrics.

New research network on fertility development

The new research network “Register-Based Fertility Research Network” initiated by MPIDR aims to provide this deeper understanding by analyzing rich register and register-like data. Main focus points on the individual level will be on trends by socioeconomic factors of females, males, or couples; and the effects of selective internal and international migration on fertility in high and less developed areas. At the contextual level, the main emphasis will be on fertility trends by the economic situation, and by access to child care.

More information and downloads

Data: Total fertility rates of the european regions from 1990 to 2012 as Excel file (XLSX File, 224 kB)

Chart Birth rates and income 1992 as vector graphics (PDF File, 131 kB)

Chart Birth rates and income 2012 as vector graphics (PDF File, 128 kB)

Original publication: Jonathan Fox, Sebastian Klüsener, Mikko Myrskylä: Is a Positive Relationship Between Fertility and Economic Development Emerging at the Sub-National Regional Level? Theoretical Considerations and Evidence from Europe, European Journal of Population, DOI 10.1007/s10680-018-9485-1

Nature publication from 2009: Mikko Myrskylä, Hans-Peter Kohler, Francesco C. Billari, Advances in development reverse fertility declines, Nature, 2009, DOI 10.1038/nature08230