July 17, 2013 | News | New Publication

For the first time, higher life expectancy is reported for East Germany

Middle-aged West German women smoke more and die earlier

(The following text is based on the original article "Reversing East-West mortality difference among German women, and the role of smoking. International Journal of Epidemiology 42(2013)2, 549-558" by MPIDR researchers Mikko Myrskylä and Rembrandt Scholz has also been published in the issue 02/2013 of the demographic quarterly Demografische Forschung aus Erster Hand.)

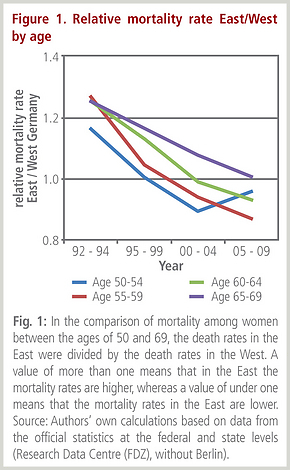

In 1989, the differences were still very clear: Germans who lived in the western part of the country lived an average of 2.5 years longer than their counterparts in the East. But eastern Germans have caught up considerably in recent decades. For the first time, women in the East between the ages of 50 and 64 have lower mortality than women in the West.

This surprising result was presented in a recent study by Rembrandt Scholz and Mikko Myrskylä of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock (see Fig. 1).

Their findings call into question a widespread interpretation of mortality rates in Germany: until now, it was assumed that the improved social, economic, and medical conditions after reunification were the main factors that drove the decline in death rates in eastern Germany. Against this backdrop, German reunification has been seen as a “natural experiment” which shows to what degree life expectancy is influenced by medical care, living standards, psychosocial stress levels, and preventive care. While previous explanations for the decline in death rates in the East have mainly cited these four factors, it is now no longer possible to assume these are the only reasons for the decrease, as in all four areas conditions in the West continue to be better than in the East, despite efforts to bring them to the same level. It therefore appears that these factors only partially explain the convergence of the mortality rates, and that there must be another reason for the reversal of these ratios the two researchers have now found among middle-aged women.

Scholz and Myrskylä thus decided to investigate a factor that is completely unrelated to reunification: smoking behavior. Although it is well-known from national and international comparisons that nicotine consumption often plays a key role in differences in mortality rates, this factor had previously been ignored in East-West comparisons in Germany.

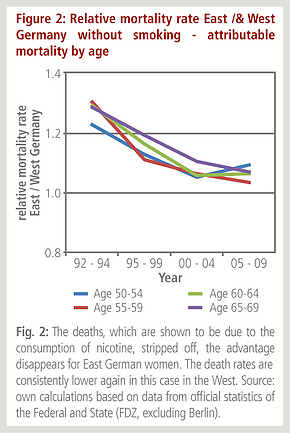

As Scholz and Myrskylä were able to show using a detailed regional analysis of the causes of death and the mortality rates in the period from 1992 to 2009, there were in fact differences in smoking behavior that led to a higher life expectancy among East German women. Among the cohorts from 1946 to 1950, for example, 44% of West German women smoke, compared to just 30% of their East German counterparts. The results of this gap could, of course, only be detected after these cohorts had reached the more mature ages at which the effects of smoking become noticeable: from 2005 to 2009, one-quarter of all deaths among 50- to 64-year-olds in the West could be attributed to smoking, compared to only 12% to 14% of deaths among the corresponding group in the East. In order to determine whether the deaths were attributable to nicotine consumption, the demographers used a well-established method in which the numbers of lung cancer deaths were used as an indicator for smoking-related mortality. After this share of the mortality rates is subtracted, the advantage among East German women disappears (see Fig. 2). This is because around one-third of the adjustment among 50- to 64-year-olds is attributable to smoking behavior.

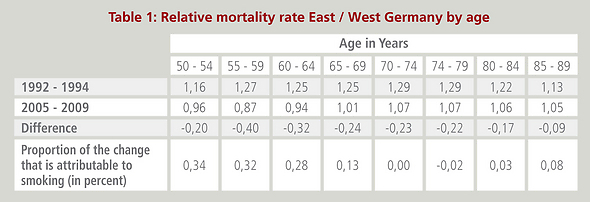

Tab. 1 Although the relative East/West mortality rate has been declining in all age groups since the 1990s, the gap between the East and the West has been shrinking overall. Thus, the greater the value is, the higher the death rates are in the East compared with the death rates in the West. It is apparent that the decline in the differences among women between the ages of 50 and 65 is in large part attributable to smoking-related mortality. Sources: Authors’ own calculations based on data from the official statistics at the federal and state levels (Research Data Centre (FDZ), without Berlin).

Such large effects could not, however, be found among older women, as the smoking behavior of these cohorts did not differ as sharply between West and East. Even so, thanks to their lower nicotine consumption, the 65- to 69-year-old East German women have the same mortality levels as their counterparts in the West. Yet among cohorts of higher ages, this effect gradually disappears (see Tab. 1). Among those under age 50 and over age 90, the effects of smoking behavior on mortality are so small that these age groups are no longer included in the study.

By contrast, investigating the outlook for younger age groups is more interesting: women in who were born in the 1960s and 1970s are just starting to reach the ages at which nicotine consumption starts to have an effect on mortality rates. Rembrandt Scholz and Mikko Myrskylä therefore anticipate that the trend could once again reverse, as East German women currently smoke more than West German women.