October 31, 2014 | News | New Publication

No work, no children?

Men and well-educated women in particular tend to delay starting a family if they are unemployed.

(The following text is based on the original article "no children no work" by MPIDR researcher Michaela Kreyenfeld and has also been published in the issue 3/2014 of the demographic quarterly Demografische Forschung aus Erster Hand.)

Earlier studies could find little or no evidence that unemployment influences family planning. But a new investigation by the German-Swedish research team of Michaela Kreyenfeld and Gunnar Andersson shows that among the unemployed, the decision about whether or not to have children depends to a large extent on the sex, age, and educational attainment of the individuals studied.

For decades, almost all western European countries have struggled with low birth rates. In Germany, the average woman had two to three children during the baby boom era of the 1960s, but today has only around 1.4 children.

In neighboring Denmark, the situation at the start of the 1980s was similar to that of West Germany: the birth rates in both countries were low. Today, however, the average Danish woman has almost 1.9 children. Sociologists attribute this recovery in the birth rate over the last three decades to Denmark’s efforts to integrate even young mothers into the labor market.

But how does unemployment affect the number of children Germans and Danes are having today? Michaela Kreyenfeld of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock and her Swedish colleague Gunnar Andersson of Stockholm University have investigated this question. In their study, published in the journal Advances in Life Course Research, the demographers formulated three hypotheses. First, they assumed that unemployment would prevent young men and women in particular from starting a family, and that the financial insecurity associated with not having a job would discourage existing families from having a second or third child.

Second, the researchers posited that the decision about whether or not to have a child would depend on the educational level of the unemployed woman: whereas a well-educated woman might be more likely to delay starting a family, a woman without a good education might see motherhood as a new and meaningful role. The demographers assumed there would be a similar, but less pronounced effect among men.

In their third hypothesis, the researchers suggested that the differences between men and women might be smaller in Denmark than they are in Germany. The demographers therefore deliberately chose to focus on two countries in which the gender roles in the family are very different. Whereas men in Germany tend to see themselves as the main breadwinner in the family, in Danish households there is a more egalitarian division of responsibilities.

To test their hypotheses, Kreyenfeld and Andersson used data from the GSOEP (German Socio-Economic Panel), an annual survey of more than 12,000 private households in Germany, which covered the period 1984-2011. For Denmark, they used data from the Danish population registers for the years 1981-2001.

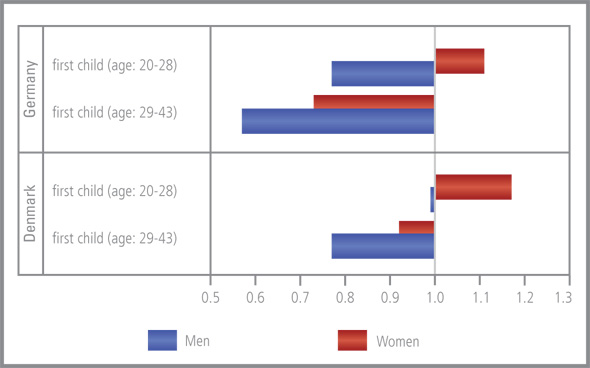

Fig. 1: The bar graph shows how unemployment affects the first birth rate among men and women of different ages in Germany and Denmark. Values below one indicate the rate is reduced with respect to men and women who are not unemployed. Values above one indicate an increased rate. © Sources: GSOEP 1984-2011, Danish register data 1981-2001, the authors’ own calculations.

Over the study period, the births of 1,931,861 children were recorded in the Danish population registers. By contrast, only 6,142 births were recorded in the social science survey GSOEP between 1984 and 2011. Kreyenfeld and Andersson nonetheless decided not to use German register data because they contain no information about the number of children born to men, and provide insufficient information about the educational levels of both men and women.

The findings showed that, as expected, men who were unemployed often delayed starting a family (see Fig. 1). But contrary to expectations, the results also indicated that this effect was less pronounced among younger men aged 20-28 than among older men. Overall, however, the findings confirmed the researchers’ initial assumption that unemployment would have a greater effect on the family planning decisions of men in Germany than of men in Denmark.

Among women, the picture was somewhat different. Whereas employment status had little influence on the decision about whether or not to have a first child among younger German women, young unemployed women in Denmark were more inclined to enter motherhood. From the age of 29 onward, however, being unemployed was more likely to prevent women from having a first child. In Germany, the first birth rate among unemployed women in this age group was found to be 30% lower than among employed women.

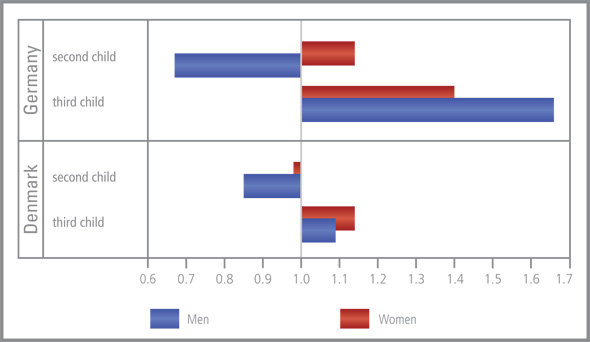

Fig. 2: The bar graph shows how unemployment affects the second and third birth rates among men and women in Germany and Denmark. Values below one indicate the rate is reduced with respect to men and women who are not unemployed. Values above one indicate an increased rate. © Sources: GSOEP 1984-2011, Danish register data 1981-2001, the authors’ own calculations.

For the birth of a second or a third child, the influence of unemployment appears to be very different (see Fig. 2). As expected, the analysis showed that unemployed men were less likely than employed men to have a second child, and that the relationship between employment and having a second child was stronger in Germany than in Denmark. But for the birth of a third child, the effect of unemployment was, contrary to expectations, shown to be reversed in both countries.

Among German women, being unemployed was found to increase the chances of having a second or even a third child. But among Danish women, employment status affected only the decision to have a third child. “Particularly striking was our finding that many mothers in Germany withdrew from working life after having just one child,” Kreyenfeld said. It was not unemployed women who were shown to be more likely to have a second or third child, but rather women who were no longer participating in the labor market.

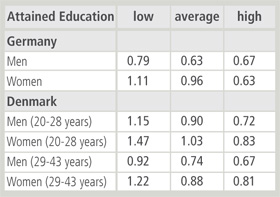

When the researchers looked at how educational attainment affected the decision about whether or not to have children, they found that their initial assumptions were generally confirmed (see Table 1). Among Danish women aged 20-28 with low levels of education, the first birth rate was 50% higher for those who were unemployed than for those who had a job. But among Danish women in this age group with high levels of education, being unemployed was associated with a reduction in the first birth rate of almost 20%.

The table shows how educational attainment affects the first birth rate among unemployed men and women in Germany and Denmark. Values below one indicate the rate is reduced with respect to men and women who are not unemployed. Values above one indicate an increased rate. Because of the small number of cases in Germany, there is no breakdown into different age groups for that country. © Sources: GSOEP 1984-2011, Danish register data 1981-2001, the authors’ own calculations.

The researchers observed comparable, though less marked effects among Danish men. Surprisingly, young, poorly educated men who were unemployed were especially likely to become fathers, Kreyenfeld and Andersson reported.

In Germany, the results for women were similar to those in Denmark. However, because of the smaller number of cases, the researchers did not break down the results into age groups. The findings indicated that the effect of education was less pronounced among German men than among German women, but that the general trends were the same.

Overall, the study found that unemployment in countries as different as Germany and Denmark nonetheless had similar effects on family planning, Kreyenfeld and Andersson wrote. As expected, they found that people in both countries had very different reactions to unemployment based on their educational attainment.

To help us better understand the social and political implications of these findings, the demographers called for additional studies to be conducted which follow the women who decided to have children despite being unemployed. “We would like to know whether these women have children because the point at which they start a family has little relevance for their professional career in any case, or whether they are seeking to maneuver their way out of the labor market,” Kreyenfeld said.

More Information

Kreyenfeld, M., Andersson, G.: Socioeconomic differences in the unemployment and fertility nexus: evidence from Denmark and Germany.Advances in Life Course Research (2014). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.alcr.2014.01.007