May 16, 2022 | Press Release

Demographic Analysis Reveals the Long Shadow of Genocide in Guatemala

Altar commemorating the victims of 1982 Maya Achi genocide in Guatemala. © Vivian Guzman

What are the long-term consequences of genocide for survivors? A new study by MPIDR researcher Diego Alburez-Gutierrez documents the mortality toll from the Maya Achi genocide in Guatemala and the role that it may play for historical memory.

“I started working on this topic because I wanted to understand the social consequences of mass violence for survivors”, says Diego Alburez-Gutierrez, Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in Rostock, Germany.

His recent study, published in the high-impact journal Demography, focuses on the long-term impacts of genocide among the Maya Achi people, who suffered a series of state-sponsored massacres in the context of the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996).

One-third of the population was killed, but two-thirds were left bereaved

The first part of the study documents, for the first time, the mortality toll of the genocide by age, sex, and socio-economic status. This has a great historical significance for a country like Guatemala, where most of the wartime atrocities lack official recognition from state authorities.

The second part of the study explores the relationship between excess mortality—deaths that would not have happened without the genocide—and family bereavement. Diego Alburez-Gutierrez finds that one-third of the population was killed in the genocide, but two-thirds lost at least one family member as a result.

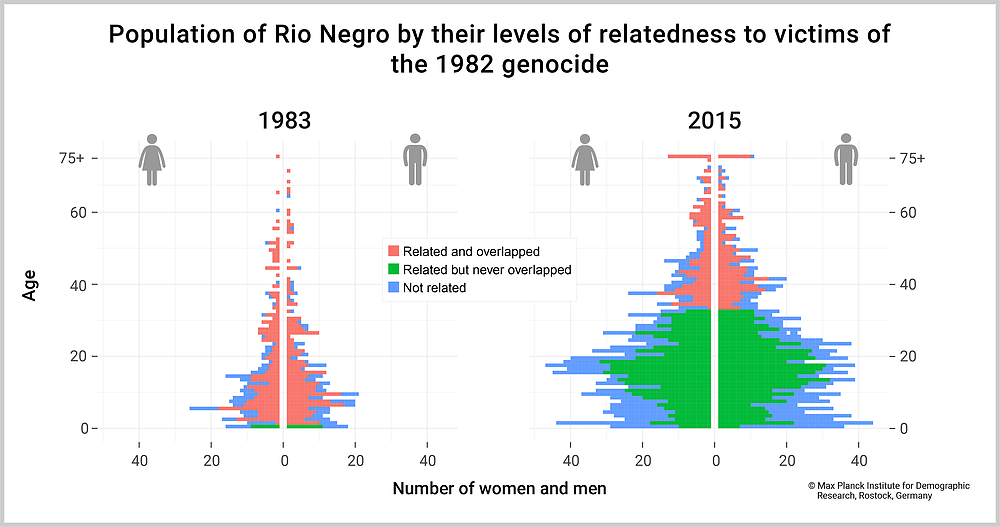

Population pyramids of the village of Rio Negro, Guatemala in the aftermath of the genocide (left) and 33 years after the violence (right). Individuals (tiles) are colored according to their relatedness to a genocide victim. © MPIDR

Download Figure (PNG File, 236 kB)

More revealing still are the long-term trends: The researcher shows that the proportion of the population related to a victim did not change between 1983, the year after the massacres, and 2015, the year in which Diego Alburez-Gutierrez collected the data. This shows how family dynamics can help to keep the memory of an event alive for decades.

The main data source were 100 genealogical interviews, which the researcher conducted with genocide survivors in the village of Rio Negro, Guatemala. This included data on 3,566 individuals and 1,986 marriages. Diego Alburez-Gutierrez compared the interview data with two local censuses with individual-level data on the population of Rio Negro. The first census was conducted in 1981, one year before the genocide, and the second one was conducted in 2008, 26 year after the genocide.

“I interpret the persistence of bereavement in two ways. First, it is an example of how disasters echo across generations and within families. Second, it can be seen as a driver of historical memory, providing a direct connection to the genocide to young members of a population who were born thereafter”, says Diego Alburez-Gutierrez.

Original Publication

Alburez-Gutierrez, D.: The Demographic Drivers of Grief and Memory after Genocide in Guatemala. Demography (2022). DOI: 10.1215/00703370-9975747

Author and Affiliation

Diego Alburez-Gutierrez, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock