January 17, 2023 | Press Release

Perceived Fairness

Evaluation of relationship satisfaction is based on perceived rather than actual fairness of labor division. © iStockphoto.com/ljubaphoto

The world of a couple changes fundamentally after childbirth. Whether the partners are as satisfied with their relationship then as they were during their childless phase hinges in part on how fair they perceive the division of labor to be. If women consider the work load as stable unfair, their relationship satisfaction drops markedly after the birth of a child. This does not apply to men, however.

Often, it only takes a small trigger for a big fight: The laundry is piling up, the breakfast board hasn’t been cleared away, doing overtime at work. Sooner or later, almost all couples will have a quarrel over the division of labor, be it paid work, be it unpaid caretaking, be it unpaid housework. The extent to which these disputes strain relationships between heterosexual couples hinges on whether the arrangement is perceived as just by the male or female partner rather than on the hours of work done. This shows a study by Nicole Hiekel from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Katya Ivanova from Tilburg University in the Netherlands. The authors present some results that are at first very surprising.

It is not surprising and it is widely known that partnership satisfaction after childbirth on average drops a little for both men and women. The two scientists looked at data from the Pairfam family panel. They found that on a scale ranging from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied), childless men rate their relationship with a mean of 8.34 points, and childless women with a mean of 8.48. When a child is born, satisfaction drops on average by 0.26 points (men) and 0.35 points (women). These average values at first seem small, but the authors show that the variance between different groups of respondents is substantial in terms of both the perceived fairness of labor division and relationship satisfaction at post-birth.

For instance, a fifth of respondents even expressed increased relationship satisfaction after childbirth, a third did not report any change, and around half of the respondents reported a decline in relationship satisfaction.

Against this background, the authors of the study pursued two key questions: They first analyzed the extent to which relationship satisfaction is also tied to post-birth labor division being perceived as more just or more unjust. They next examined the degree to which these perceptions and assessments) are moderated by the gender role attitudes of the respondents.

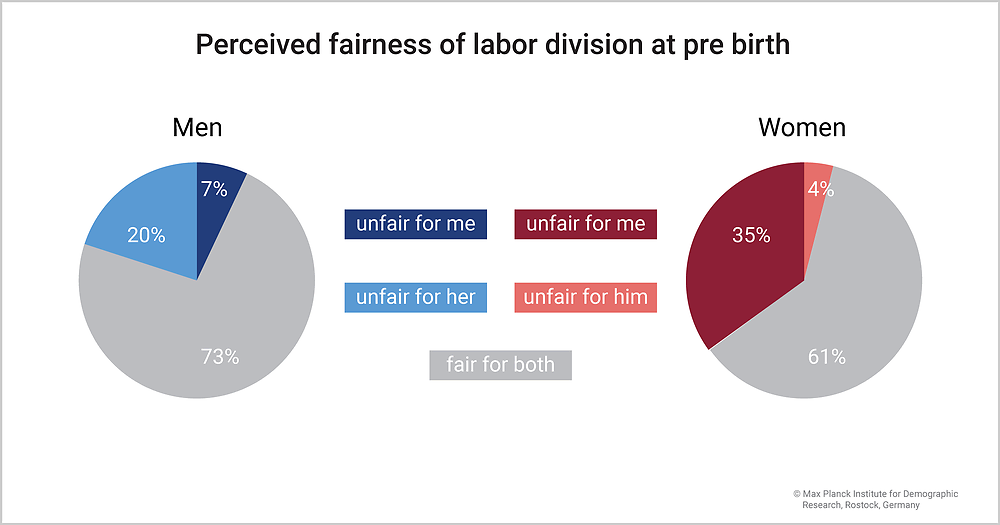

Before having a child, most couples still perceive the division of labor as fair.

Source: Pairfam 11.0, own calculations. © MPIDR

Download Figure (PNG File, 99 kB)

Overall, the proportion of those who perceive the labor division in the partnership to be fair is relatively large – especially prior to the birth of a child and especially among men: Three out of four say that the workload is distributed fairly. For women, the figure is significantly lower, at 62 percent. After the birth of a child, 60 percent of the men and almost 50 percent of the women still feel this way.

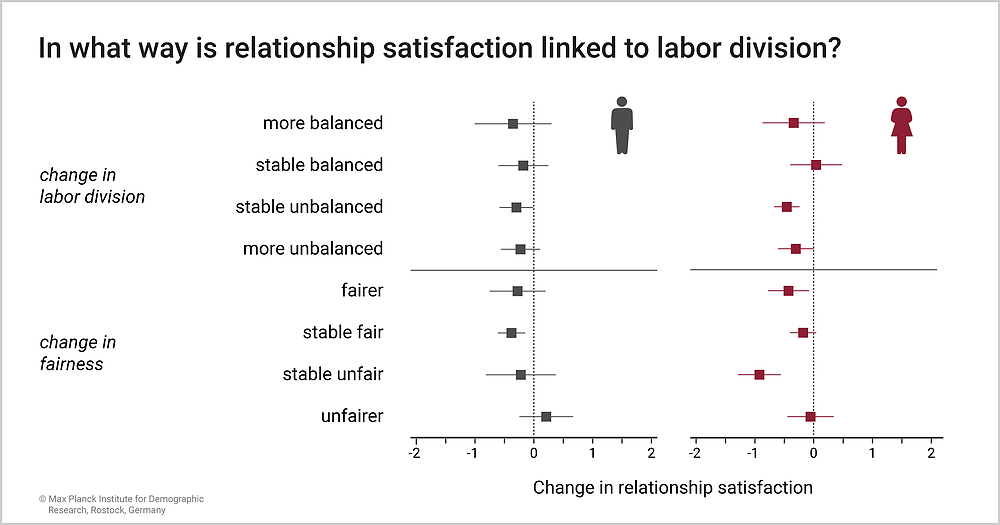

The degree to which satisfaction changes hardly depends on the actual workload. For instance, if tasks are shared more equally after the child was born, women are not more satisfied with their relationship than in a partnership where work is distributed more unequally after the birth of the child. The same holds true for men.

Changes in the actual labor division have little impact on changes in relationship satisfaction. But perceived fairness does. Source: Pairfam 11.0, own calculations. © MPIDR

Download Figure (PNG File, 95 kB)

The story is very different when it comes to perceived fairness, at least for women: For those, who find their division to be a stable fair arrangement throughout the fertility transition, satisfaction hardly changes. But for women who consider their workload as stable unfair, post-birth satisfaction decreases by almost a full point, i.e., around three times as much as the average drop in relationship satisfaction. No change can be observed for men, however; possibly because both male and female respondents agreed that the women under-benefits when the division of labor is considered unfair.

Surprisingly, women are not more satisfied with their relationship when the perceived fairness in labor division increases after family formation. The opposite is more likely to be true, although the differences are not statistically significant. If the perceived fairness decreases, no significant change can be observed either.

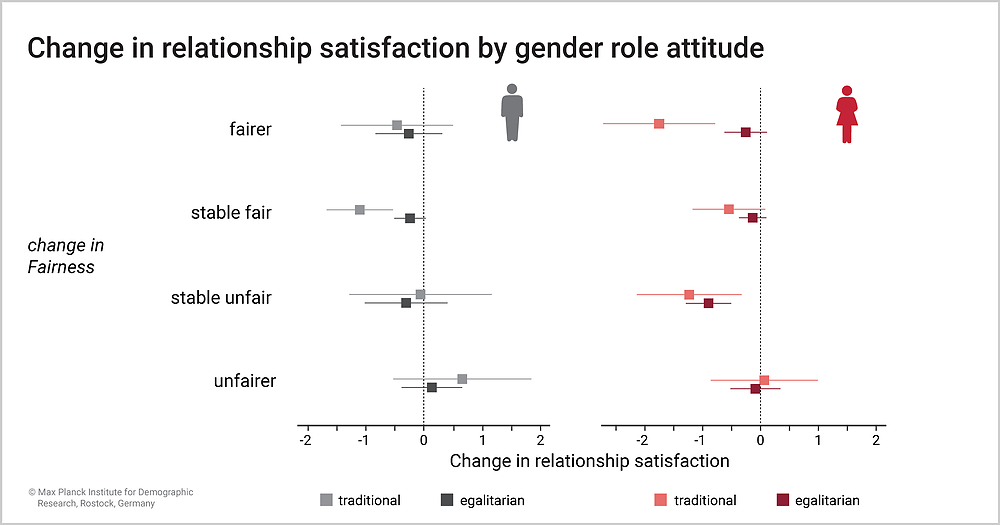

To investigate these results, which at first glance seem surprising, the two demographers also consulted data on gender role attitudes. The Pairfam study records respondent answers to questions and statements such as: Men should participate in housework to the same extent as women. If the respondents agreed with the statement, the researchers considered them to have egalitarian gender role attitudes. In further analysis they thus found that changes in relationship satisfaction among men in the context of changes in perceived fairness is strongly associated with men’s individual gender role attitudes.

Perceived fairness in the division of labor is specifically conducive to the relationship satisfaction of women and men with an egalitarian gender role attitude. Those who perceive the division of labor in their partnership as (increasingly) fair and have an egalitarian gender role attitude show no decline in relationship satisfaction after the birth of a child. Source: Pairfam 11.0, own calculations © MPIDR

Download Figure (PNG File, 83 kB)

Among men with egalitarian gender role attitudes who considered the division of labor as stable fair, relationship satisfaction hardly changed. But among men with a traditional understanding of gender roles, a fair arrangement was associated with a significant drop in relationship satisfaction. For this group, it dropped as much as four times the average.

The differences among women are even more pronounced: The satisfaction of women with egalitarian gender role attitudes hardly changed when the division of labor was felt to be fairer after the birth of a child. Among traditionally minded women, however, satisfaction sank by a full 1.76 points.

The authors surmise that an arrangement perceived as stable fair contrasts more strongly both the expectations of traditional men towards parenthood and the prevailing gender role attitudes observed in society as a whole. By the same token, being under-benefitted as a mother just a little is at odds with the expectations of traditionally oriented women. These results show that the mismatch between imagined and lived realities can have an impact on the well-being of couples far beyond the de facto division of labor.

Original Publication

Hiekel, N., Ivanova, K.: Changes in Perceived Fairness of Division of Household Labor Across Parenthood Transitions: Whose Relationship Satisfaction Is Impacted? Journal of Family Issues (2022). DOI: 10.1177/0192513X211055119

Authors and Affiliations

Nicole Hiekel, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock

Katja Ivanova, Tilburg University