July 02, 2025 | Press Release

Rapid Demographic Changes Reshape Family Structures

MPIDR study: Accelerated demographic change is creating significant differences in the number of relatives between peers of similar ages

Declining birth rates and rising life expectancy are reshaping the size and age structure of families worldwide. A recent study reveals that the question is not only whether these changes will occur, but also how quickly they will unfold. Analyses of real population data from Thailand, Indonesia, Ghana and Nigeria as well as stylized scenarios confirm this trend. In countries undergoing rapid demographic change, people with an age difference of only five to ten years may have drastically different kinship networks. The swift decline in, and evolving age structure of, these networks can significantly weaken traditional chains of mutual family support.

Even if they are no more than five years apart, near-age peers will have a very different number of cousins or daughters. © iStockphoto.com / DisobeyArt

- As birth rates decline and life expectancy increases, the differences in the number and age structure of relatives grows, even among individuals of similar ages.

- In Thailand, rapid demographic change has led individuals born just 5 to 10 years later to have 30% fewer cousins and 15% fewer daughters than their older counterparts.

- Rapid demographic transitions quickly erode informal support networks. Without early institutional alternatives, significant care gaps and inequalities between cohorts may arise.

The dynamics of family structure is undergoing a transformation. Declining fertility and mortality rates are leading to new kinship configurations worldwide. But how quickly are changes taking place? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR), Stanford University in Stanford (USA) and Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan (China) have explored this critical question. In a recent study, the researchers analyzed how the speed of demographic change influences the number and age distribution of a person's relatives. Their findings indicate that peers of similar ages may end up with drastically different kinship networks in the face of rapid demographic change.

“Using advanced demographic tools to model kinship relationships over time, our research addresses a crucial question: Can two individuals who are only five or ten years apart in age possess entirely different family structures? Our findings confirm that the answer is ‘yes’, which has profound implications for individuals and society,” explains Sha Jiang, author of the study and a researcher in the research group of Kinship Inequalities and the laboratory of Digital and Computational Demography at MPIDR. Jiang and her colleagues' analysis drew from two sources: empirical data from four countries at varying stages of demographic transition (Thailand, Indonesia, Ghana, and Nigeria), and stylized scenarios designed to isolate variables by controlling the speed of change in either fertility or mortality while keeping the other constant over time.

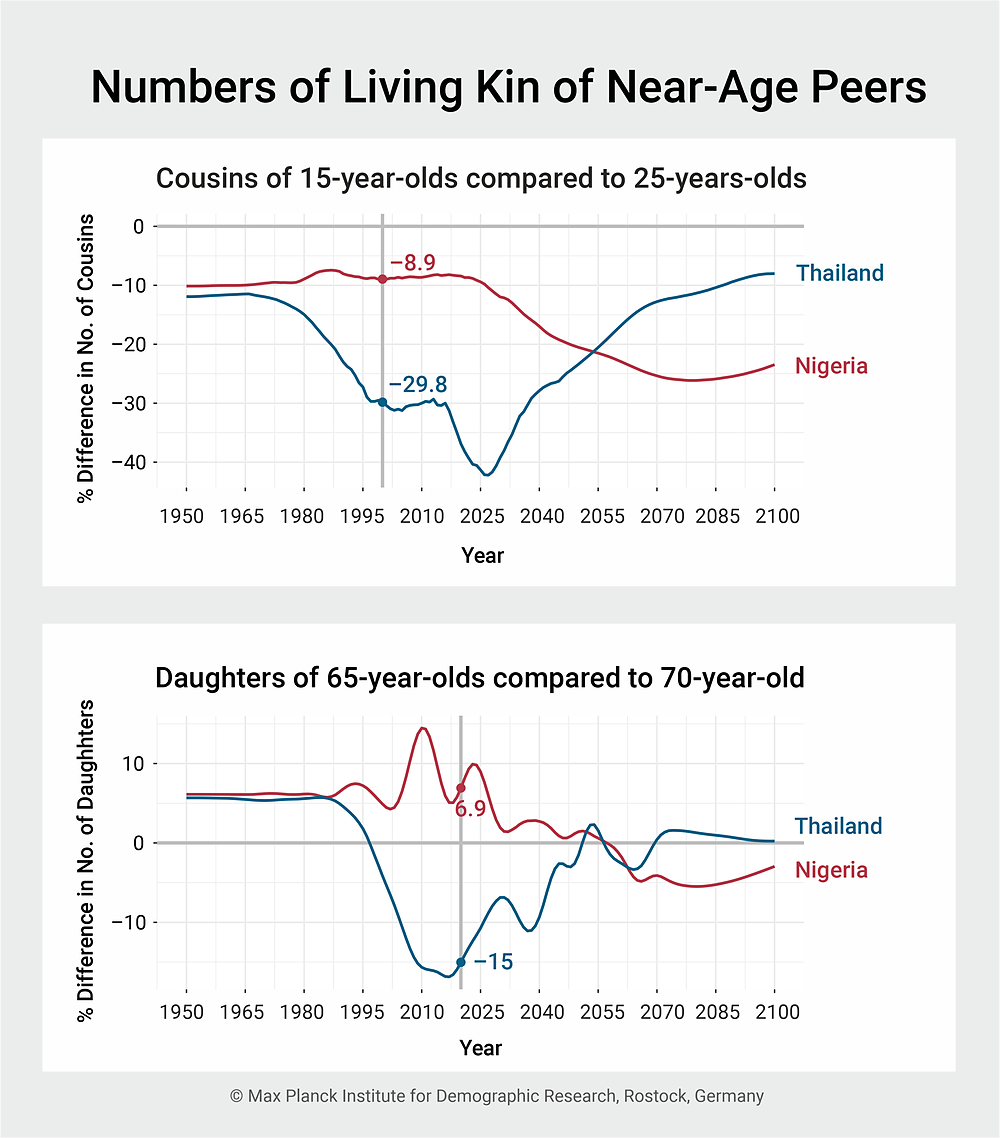

Percentage difference in the expected number of living relatives. The upper figure illustrates the difference in the expected number of living cousins between 15- and 25-year-old focal individuals. The lower figure shows the difference in the expected number of living daughters between 65- and 70-year-old focal individuals.

© MPIDR

Shrinking families and rising inequality

As birth rates decline and life expectancy rises, families are being reshaped, becoming more vertical with more living generations but fewer relatives within each. “Our research uncovers a crucial factor in this global trend that has been largely overlooked: the speed of this demographic change. The rapid pace of these changes can fundamentally alter family networks,” Jiang explains.

The study's key finding indicates that the faster the demographic change, the wider the gap between individuals of a similar age regarding the number of living relatives they have. When change occurs slowly, it is spread over several decades. However, Jiang and her colleagues found that significant and abrupt differences emerge when change happens rapidly within a single generation.

“Our analysis draws on data from countries like Thailand, which has undergone rapid demographic changes, particularly a significant decline in the birth rate, and Nigeria, where changes have been much slower,” said Jiang. In Thailand, for instance, a 15-year-old in 2000 had, on average, almost 30% fewer living cousins compared to a 25-year-old. In Nigeria, this difference was much less pronounced, at under 10%. By 2020, a 65-year-old in Thailand had, on average, 15% fewer daughters than a 70-year-old. In Nigeria, however, the trend was reversed: the 65-year-old had about seven percent more daughters than their older counterpart.

Care gaps arise when family networks break down more quickly

This stark contrast illustrates how demographic change is taking place differently around the world. The differences extend beyond the number of relatives to include age structure as well. Rapid transitions lead to dramatic changes to both the average age and age composition of relatives. “New generations have fewer relatives and their relatives are also different in age composition to those of previous generations," Jiang continues. This shift directly impacts the dynamics of intergenerational support within the family.

The results of this study make it clear that rapidly changing demographics require early action in terms of institutional support for the care of relatives. “Informal networks between cohorts are breaking down more quickly. The speed of demographic change is creating significant inequalities in family support resources between neighboring cohorts. This raises important questions of fairness in the design of social systems. Societies undergoing rapid change must accelerate the development of alternative support mechanisms to prevent disadvantaged groups from falling through the cracks in traditional family networks,” concludes Sha Jiang.

Original Publication

Sha Jiang; Wenyun Zuo; Zhen Guo; Shripad Tuljapurkar: Changing Demographic Rates Reshape Kinship Networks in Demography (2025); DOI:10.1215/00703370-11996578

Contact

Sha Jiang

Research Scientist

Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR)

Jiang@demogr.mpg.de

Silvia Leek

Head of Public Relations and Event Organization

+49 (0)381 20 81 143

press@demogr.mpg.de

Keywords

Kinship networks, Demographic rates, Transition speed, Time-varying